Two reports came out on 21st May which was also, incidentally, my birthday. The first was the report of the Environmental Audit Committee's inquiry into the Green Economy. I gave evidence there on behalf of the Green House thinktank, following up on our written evidence. I was in an evidence session with David Powell from Friends of the Earth and a representative of the TUC. It is encouraging that, as well as Green House's evidence, WWF, NEF, and others were clear that a green economy will be one that respects planetary limits and recognises that we must restructure our economy so that it does not rely on perpetual growth.

The Committee chose as its media hook for the report the fact that deregulation is undermining attempts to move towards the green economy, a rather dull angle which failed to arouse much interest. The real political question of our time - whether we can ever or should ever return to growth - was ignored. Perhaps it just seemed too far from the hegemonic idea of the urgent and unassailable need to return to growth as the only solution to our economic woes.

The EAC's report focuses rather on 'current patterns of economic growth', in spite of clear evidence from Tim Jackson about the fact that decoupling growth from resource and energy use is a chimera. However, they did quote at length a list of groups who took a hardline view on growth:

'52. Many saw the Government’s current agenda as focusing too much on growth and too

little on measures to protect the environment and ensure environmental limits are not

breached. David Powell of Friends of the Earth believed that current government policies, including Enabling the Transition, were being presented as “growth first ... let’s try and make it green and anything else we can do is fantastic”. . . We also heard concerns that, without a definition of sustainable development being included within the new planning guidance, proposals to introduce a “presumption in favour of sustainable development” would lead to unsustainable development. RSPB believed greater thought should be given to whether the “continued push for growth is in fact in conflict with prosperity in the longer-term”. The Packaging Federation believed there was little sign that the Government understood a “real danger of a fundamental incompatibility between UK climate change goals and economic growth”. Green House believed that a strategy of export-led growth was incompatible with a green economy as “it relies on lengthy supply chains and hence an extensive use of energy and so contributes to climate change”.'

Our idea of 'transitional growth' was also cited: 'Green House believed that economic growth was only possible in the short-term as part of a transition strategy to move us towards an economy that is in a steady state. Such economic growth would be confined to replacing infrastructure to enable self-reliant economies stabilising the economy within our national resource limits.' And we were quoted as stating that 'because of the “unfeasible nature of the increased efficiencies required and the nature of rebound effects associated with technological improvements”, seeking to decouple economic growth and production from CO2 emissions “is an example of psychological denial”.

Oxfam also gave evidence, which brings me to the second report I wanted to draw attention to: Be Outraged: There are Alternatives, an attack on the present absurd economic policies being followed by Western nations from a group of development economists published by Oxfam. The report states 'that the austerity approach to reducing deficits and debt is counterproductive; it is leading to a downward spiral of incomes and government revenues making it more difficult to reduce the debt and undermining growth prospects.' The report is authoritative and useful in bringing together clearly and critically the consequences of misguided economic policies including: 'More than 10 per cent of European adults are unemployed, up by 50 per cent since 2008. More than one in five- 22% - youth under 25 are unemployed and in some countries over 40%' or 'Top incomes have soared in the UK and US especially: the globe’s richest 1 per cent (61 million people) earn the same as the poorest 56 per cent (3.5 billion)'.

Overall, though, the report is fairly standard Keynesian stuff and, although Oxfam gave evidence to the EAC and devote attention to the structural problems with the growth economy, this line of their work does not seem to join up with their attempts to challenge austerity politics. As the Green Party has found, resolving the tensions between social justice and a steady-state economy is not always easy, but no organisation or research institute that has understood the need to respect planetary limits should now be producing arguments for growth.

Green House is running a personalised campaign to shift the media position on this question: please join us. We are targeting the BBC, on the basis that we pay for them, and because their email addresses are easy: firstname.familyname@bbc.co.uk. Each time you hear the hysterical statement of the universally acknowledged need to return rapidly to growth, please email the person who has made this statement, giving them some links to clear statements of the destructiveness of this position. You can refer to work by Green House, the EAC report, or more broadly the website of CASSE - the Centre for the Advancement of a Steady State Economy.

.

Tweet

All other green campaigns become futile without tackling the economic system and its ideological defenders. Economics is only dismal because there are not enough of us making it our own. Read on and become empowered!

Showing posts with label steady state economy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label steady state economy. Show all posts

29 May 2012

24 May 2011

If You Can't Beat 'em Laugh at 'em

For those readers who aren't already aware of it I should point you in the direction of CASSE, the Center for the Study of a Steady State Economy. In what can be depressing times, as the refusal of the global capitalist system to respect the planet we need for our survival grows more threatening every day, they manage to maintain their campaigning and educational work with vigour, and even humour.

For those readers who aren't already aware of it I should point you in the direction of CASSE, the Center for the Study of a Steady State Economy. In what can be depressing times, as the refusal of the global capitalist system to respect the planet we need for our survival grows more threatening every day, they manage to maintain their campaigning and educational work with vigour, and even humour.Last year, a conference co-organised by the Center in Leeds produced the excellent report Enough is Enough, which not only established clearly the need to end economic growth, but also provided plans for what this would mean in different areas of economic life. Now Rob Dietz has produced a blog post lauding the achievements of the Everyman economist Dr Milton Mountebank, best known for his theoretical work Infinity and Beyond: The Magical Triumph of Economics over Physics.

From Oliver James's concept of affluenza to the New Economics Foundation's impossible hamster, we have plenty of advocates in favour of a balanced and fulfilling economy rather than an economy of endless expansion and futile progress. English Romantic poet William Wordsworth might seem an unlikely voice to add to their list, but his sonnet 'Nuns fret not' is the medium and the message. As Jonathan Porritt pointed out, nobody complains about the sonnet form because it has only 14 lines. And like the haiku and the Twitter post, a limit can provide a challenge to creativity rather than a boundary to be breached.

Here is the sonnet in full:

Nuns fret not at their convent's narrow room;

And hermits are contented with their cells;

And students with their pensive citadels;

Maids at the wheel, the weaver at his loom,

Sit blithe and happy; bees that soar for bloom,

High as the highest Peak of Furness-fells,

Will murmur by the hour in foxglove bells:

In truth the prison, unto which we doom

Ourselves, no prison is: and hence for me,

In sundry moods, 'twas pastime to be bound

Within the Sonnet's scanty plot of ground;

Pleased if some Souls (for such there needs must be)

Who have felt the weight of too much liberty,

Should find brief solace there, as I have found.

. Tweet

5 April 2011

Elite's Marginal Productivity Challenged by Nobel Renegade

In spite of the fact that he is clearly right, and that he is in the sort of position where holding critical views could have some impact, I cannot feel warm about Joseph Stiglitz. It must be the years he spent at the World Bank drawing a fat salary while the Bank's policies caused starvation and death. Although the black mark is partially expunged by his dissent and subsequent sacking, it still recalls a bank boss who takes his large pension and then joins the Rotary Club after retirement. And of course Stiglitz has never returned his 'Nobel Prize', suggesting he still revels in the acclaim of his dubious peers.

In spite of the fact that he is clearly right, and that he is in the sort of position where holding critical views could have some impact, I cannot feel warm about Joseph Stiglitz. It must be the years he spent at the World Bank drawing a fat salary while the Bank's policies caused starvation and death. Although the black mark is partially expunged by his dissent and subsequent sacking, it still recalls a bank boss who takes his large pension and then joins the Rotary Club after retirement. And of course Stiglitz has never returned his 'Nobel Prize', suggesting he still revels in the acclaim of his dubious peers.But bitterness aside, let's enjoy his latest offering published in this month's Vanity Fair. The article begins with the commonplace and yet shocking statistic that the top 1% of US citizens take nearly a quarter of the country's income each year and own 40% of its wealth. As recently as 1986 the comparable figures were 12% and 33%. This extraction of value by the plutocrats has been bought largely at the expenses of the professionals.

There is a useful phrase in the article which I think we could make much of: 'Trickle-down economics may be a chimera, but trickle-down behaviorism is very real.' The lifestyles of the wealthy, which in an earlier age we would have considered beyond our station, are now advertised to us as something to aspire to. Such luxuries and long-haul flights and fast cars are considered as rights, and greens who suggest that they may need to be restricted are painted as killjoys if not oppressors.

Stiglitz argues rightly that the justification for the growth in inequality on the basis that wealth creators have to be rewarded so that the economy can boom, and that this additional output will benefit us all, is unsupported by evidence. What he fails to notice, and what makes the need to end the extraction of value by the wealth so urgent, is that this economic growth is actually undermining the conditions that enable any economic activity at all to take place.

This is the argument offered by the eco-socialists, their so-called 'Second Contradiction of Capitalism'. A green economist would probably find a more grounded and passionate response: the greed of the wealthy, and the economic growth it is linked to, is killing the planet and destroying all our lives.

. Tweet

25 November 2010

The Happiness Crusade

The demonstration I was on yesterday in Cardiff was so much fun it went on all night. If you are a tweeter you can support the protest by sending a message of support. The demonstration was lively, noisy and made up of a mixed bag of students and schoolkids, leavened with a mix of Marxists, socialist workers and Greens. We were already well into chanting when the younger students arrived in their own march to great cheers - what somebody on the Twitter feed has called 'the children's crusade'.

Protesting is turning out to be so much fun that it makes me wonder whether this is part of Cameron's reason for beginning to measure happiness since, as the graphic shows, close social connections make people happier than money, once their basic needs are met (thanks to nef for the graphic, and their leading research in this area). Labour's creation of the disturbingly oxymoronic position of Happiness Tsar has been taken up by the Condems who have instructed their national statistician to begin a programme of scientific measurement of how jolly we all are.

Unlike in Bhutan, however, happiness is not to become the focus of policy-making, merely an adjunct to the measure of economic growth which is, as the PM will tell us later today, the real source of all our aspirations. If Richard Douthwaite was right in his seminal book The Growth Illusion in establishing that, beyond a certain point, growth actually detracts from our happiness, then this is a circle that simply cannot be squared. Instead we need to be developing policies for the post-growth world, as in the recent example of participatory policy development at the Leeds Steady State Economy conference, whose report was recently published.

. Tweet

Protesting is turning out to be so much fun that it makes me wonder whether this is part of Cameron's reason for beginning to measure happiness since, as the graphic shows, close social connections make people happier than money, once their basic needs are met (thanks to nef for the graphic, and their leading research in this area). Labour's creation of the disturbingly oxymoronic position of Happiness Tsar has been taken up by the Condems who have instructed their national statistician to begin a programme of scientific measurement of how jolly we all are.

Unlike in Bhutan, however, happiness is not to become the focus of policy-making, merely an adjunct to the measure of economic growth which is, as the PM will tell us later today, the real source of all our aspirations. If Richard Douthwaite was right in his seminal book The Growth Illusion in establishing that, beyond a certain point, growth actually detracts from our happiness, then this is a circle that simply cannot be squared. Instead we need to be developing policies for the post-growth world, as in the recent example of participatory policy development at the Leeds Steady State Economy conference, whose report was recently published.

. Tweet

17 June 2010

Celebrating Zero Growth

I spent yesterday evening at the launch of the second Zero Carbon Britain report, a second edition of the report again produced by the Centre for Alternative Technology, this one intended to frame our transition to a climate-friendly society by 2030. There is lots of good stuff here, with detailed plans for the obvious areas like built environment, transport and energy, and more on the less obvious areas such as agriculture, motivation and policy than the last time the report was put together.

I spent yesterday evening at the launch of the second Zero Carbon Britain report, a second edition of the report again produced by the Centre for Alternative Technology, this one intended to frame our transition to a climate-friendly society by 2030. There is lots of good stuff here, with detailed plans for the obvious areas like built environment, transport and energy, and more on the less obvious areas such as agriculture, motivation and policy than the last time the report was put together.I was invited to contribute to the economics chapter, which was an additional area, but I am sorry to say that none of my contributions seem to have made it into the report. One reason for this is that the cultural home of Zero Carbon Britain as a study - and even as a concept - is the rather tecchie world of modelling and gadgets, a world where my approach must seem rather girlie. The deeper reason is that the report was intended to influence government, and it was therefore self-consciously set within the existing paradigm.

My question to the report's writers is: can we have a Zero-Carbon Britain unless we have a Zero-Growth Britain. In spite of the fact that the job of writing the economics chapter was delegated to nef, and they have clearly stated elsewhere that a steady-state economy is a prerequisite of sustainability, this question caused some confusion at the launch and is not adequately addressed in the report. A decision had been made to frame the report in terms that parliamentarians would feel comfortable with, so the growth paradigm was left unchallenged.

Economics is an expert field, perhaps even a field whose jargon and mathematical symbols operate like a 'Trespassers will be prosecuted' sign, but it is desperately important that those who would propose sustainability policies in any area have a basic level of economic literacy. There is little point in talking about changes to housing, energy or transport without stating simultaneously that all these changes will be irrelevant if we continue to live in an economic system that requires growth in order to survive.

The report was launched at the first meeting in this parliament of the All-Party Parliamentary Climate Change Group, a group who include E.On and Royal Bank of Scotland amongst their membership. I am sure that both will find opportunities for making profits from the sort of move towards a zero-carbon Britain that the report proposes, whether as installers of massive new energy grids or the providers of the capital for the same. For my money, the Steady-State economy conference in Leeds on Saturday has more relevance to our species' survival on this planet. Tweet

4 June 2010

The Ideology of the Cancer Cell

It is hard to question the prevailing view that we are on the brink of an even more serious economic collapse than the one we squeaked through some two years ago. What first emerged as a private-sector debt crisis has not been solved, it has merely been shifted into the public sector. The first round of default was solved by the publics of Western democracies taking on private debts on a previously unimaginable scale. Now that we have reached our collective overdraft limit, what are we supposed to do next?

It is hard to question the prevailing view that we are on the brink of an even more serious economic collapse than the one we squeaked through some two years ago. What first emerged as a private-sector debt crisis has not been solved, it has merely been shifted into the public sector. The first round of default was solved by the publics of Western democracies taking on private debts on a previously unimaginable scale. Now that we have reached our collective overdraft limit, what are we supposed to do next?The conventional wisdom, which is being used to determine the economic policy of our new government, is that we need to 'tighten belts'. The 'we', as usual, is loosely defined. As somebody who works for the public sector I am already having to drill new metaphorical notches into the over-strained leather. Small private-sector businesses have already fasted beyond salvation while the fat cats of the finance sector appear to still be lapping up cream.

Other economists, who are rather bizarrely are being referred to as 'radical' are resisting the cuts. Their rationale for this is entirely reasonable: cutting the public sector will choke off the recovery and force us back into a recession which is likely to be deeper and longer than the last. How will they pay for this? Their solution, which undermines the use of the 'radical' label, is to fiddle with the figures in the short term and wait for economic growth to sort the problem.

A green economist can be the only real radical, and a green economist must reject any policy that relies on economic growth to get us out of this mess. We have the advantage of a really radical proposal: restructure the global financial system so that the debt is really removed - and for good. This would ensure future stability and equity.

As green economists we can also raise two other policy options which would seem too market interventionist for orthodox economists. First, we can take charge of the banks that 'we' own and direct their lending towards domestic, small-scale and sustainable businesses. Second, we can recommend that such government money as is spent is intentionally directed towards the sectors where it will have the maximum multiplier effect. On the one hand this means increasing the wages of lower-paid public-sector workers, who are much more likely to spend the money than save it. On the other, it could mean asking serious questions about changing our approach to trade so that we control the flow of money from our failing economy to the flourishing Chinese economy. Too radical for you, Professor Blanchflower? Tweet

3 April 2009

The Paradox of Thrift

It was Keynes's view that 'Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.' He is now become the posthumous eponym of his own adage, as the economic crisis forces the resuscitation of politically unpopular measures that are no longer appropriate to our times.

Commenting on the horrific consequences of capitalism's last truly spectacular bust, Keynes noticed that people's natural response to be cautious in times of crisis could actually make the problem worse. In the typically natty way he had with language Keynes referred to this conundrum as 'the paradox of thrift'. While saving at the individual level may be entirely noble, at the level of an economy as a whole, and especially one with insufficient demand, it can be devastating. Japan is often taken to be the paradigmatic case.Wise he may have been, but Keynes did not recognise the planetary frontier and so his plans to save us from Depression through exhorting us to consume more are now dangerously outdated.

Thrift has been a concept with a serious PR problem for several decades, as built-in obsolescence and the fashion industry have generated wants and desires that were then satisfied by production and consumption. In my paper 'Sen and the Art of Market-Cycle Maintenance' I sketch the environmentally destructive consequences of this capitalistic modus operandi.

The paradox itself is easily resolved once we think our way beyond the ideology of capitalism, since its existence results from the underlying assumption that individual behaviour is only helpful if it fits in with that system's logic. We are, in reality, free to make much wider choices than whether to spend or save, or what variety of washing powder to buy. We are free to choose a whole new economic system based on balance rather than growth and justice rather than inequality. Tweet

Labels:

economic growth,

Keynes,

over-consumption,

steady state economy,

thrift

31 December 2008

Is this the year of the steady state?

The economy has ceased to grow, in fact it has begun to shrink. Interest rates are now at marginal levels and may soon drop to 0%. Combine this with the falls in stock prices and you realise that it is no longer possible to earn money from having money. These are the very characteristics of the steady state economy that greens have been calling for. So should we be celebrating?

The problem with interest and other forms of using money to make money is that it is mortgaging the future. Since money is expanding goods will need to be increased so that they are available when the people who have that money come to demand them. And all those goods need resources and energy to make them. This is an unsustainable way of running an economy.

Because of this link between expanding money supply and increasing demand for goods, in a capitalist economy unless you have constant and exponential growth the money system will collapse--as it just has done. But rather than try to reboot the money system and desperately try to stimulate more economic activity, wouldn't it be more sensible to use this opportunity to shift our economy onto a more sustainable path?

Herman Daly's concept of the steady state economy is one where you do not take more resources from the planet than can be replenished and where scarce resources are used frugally and recycled. The concept also has significant implications for the population, which needs to be stabilised. He argued that this is the only sort of economy that can be sustainable on a limited planet.

The coming year is going to be a grim and challenging one; we will see the darkest face of capitalism. But it will also offer great opportunities for those of us who have a clear vision and proposals for how to bring it to life to make those arguments. Tweet

7 November 2008

Capitalist rollercoaster

Generally in economics 'long-term trends' are anything but. I was recently in a supervision session with a colleague who was describing an econometrics method used to 'explain' the behaviour of stock-market investors. It works with long data series, but these are minutes of investment decisions! So in a day you can create a really long-term trend!

For a discipline that makes great play of the differences between short, medium and long terms, economics is remarkably poor at analysing the long run. Perhaps that is because, as Keynes so eloquently noted, in the long run we are all dead. This is not a very helpful attitude for our grandchildren or the planet they hope to inherit.

In view of this prevalent short-termism what joy it was to find the long-term trend of UK (English) interest rates on the Guardian website. I would be interested to hear others' interpretations of what we can learn from these.

What immediately captures attention is that in the early phase of the life of the Bank of England interest rates are almost completely static. Is this an image we should hold in mind when thinking of the steady-state economy? A stable long-term interest rate suggests a lasting agreement about the return that the holders of capital may demand. This seems to suggest that, prior to 1800, there was little evidence of struggle over the value in the economy.

The trend becomes increasingly haywire from 1800 onwards, as industrial capitalism began in England and conquered the world. For the past 200 years we have been living on this rollercoaster with its endless economic and social conflict. The solution is not to return to the earlier phase of stable interest rates relying on an agreement that the rich man should stay in his castle and the poor man at his gate.

Surely a more fruitful solution would be to challenge the concept of interest itself. What gives a rich person the right to become richer merely because they have wealth to begin with? Removing the ability of money to store value through time would radically change the way we behave as economic actors--it is surely a prerequisite for any steady-state economy. Tweet

16 October 2008

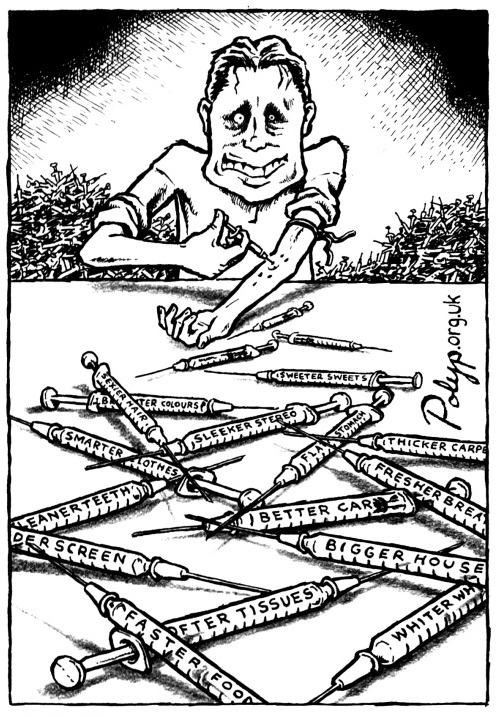

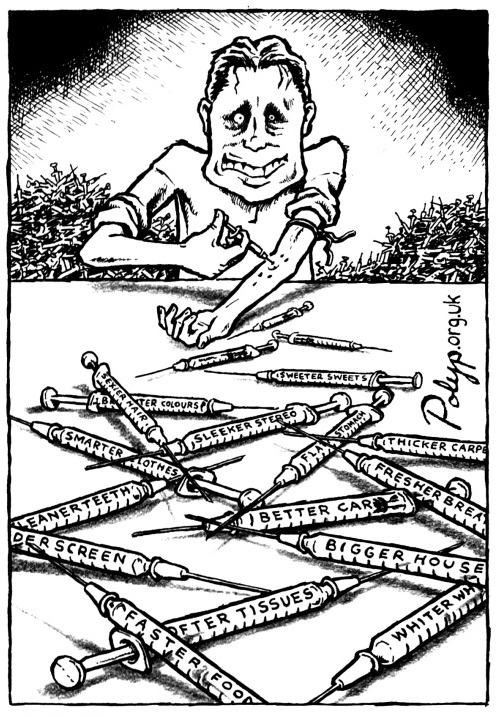

Hero or Heroin

I'm sure Gordon Brown was secretly delighted to have been compared with Flash Gordon at a recent press conference. Given his recent shady dealings with the bankster fraternity I would have thought Flash Harry was more appropriate. What would the flaming red Gordon of his student days have made of this man who is putting the poor of this country in debt to prop up a failing capitalist system?

But is it the right thing to do, to fuel capitalism's addiction to money? Isn't Gordon rather acting as a drug dealer, providing more of just what is worst for the global economy, bloated with years of excess and destroying the body it depends on?

But is it the right thing to do, to fuel capitalism's addiction to money? Isn't Gordon rather acting as a drug dealer, providing more of just what is worst for the global economy, bloated with years of excess and destroying the body it depends on?

If you will indulge my extended metaphor for a while longer, perhaps we could explore what mechanisms we might pursue to tackle the addiction, to move the economy away from its moneylust and towards a balanced steady state. What would be the methadone that we could introduce as a substitute during the transition?

Gordon is calling for a summit to debate a new financial architecture. Part of that might be Richard Douthwaite's Ebcu or environment-backed currency unit. This is a neutral currency created by agreement between the world's nations and under their control. It could contribute to a global economy where the economic power of countries was more equal; in a world dominated by the dollar this can never be the case.

But more importantly, because the ebcu is linked to emissions of carbon dioxide, it operates like a carbon standard, linking economic activity to the ability of the planet to support that activity. It follows the Contraction and Convergence model for a decline in CO2 emissions and a fair sharing of these emissions between countries.

Although the 'summit' will be exactly that - our exalted leaders meeting like so many Old Testament prophets on the mountain top - we should make our demands clear. The agreement should be for a steady-state economy that balances the interests of the people of the world, and the planet we all depend on.

[Thanks to Polyp for another brilliant cartoon. Visit his website and check out his great new animated version of the rats in the trap] Tweet

But is it the right thing to do, to fuel capitalism's addiction to money? Isn't Gordon rather acting as a drug dealer, providing more of just what is worst for the global economy, bloated with years of excess and destroying the body it depends on?

But is it the right thing to do, to fuel capitalism's addiction to money? Isn't Gordon rather acting as a drug dealer, providing more of just what is worst for the global economy, bloated with years of excess and destroying the body it depends on?If you will indulge my extended metaphor for a while longer, perhaps we could explore what mechanisms we might pursue to tackle the addiction, to move the economy away from its moneylust and towards a balanced steady state. What would be the methadone that we could introduce as a substitute during the transition?

Gordon is calling for a summit to debate a new financial architecture. Part of that might be Richard Douthwaite's Ebcu or environment-backed currency unit. This is a neutral currency created by agreement between the world's nations and under their control. It could contribute to a global economy where the economic power of countries was more equal; in a world dominated by the dollar this can never be the case.

But more importantly, because the ebcu is linked to emissions of carbon dioxide, it operates like a carbon standard, linking economic activity to the ability of the planet to support that activity. It follows the Contraction and Convergence model for a decline in CO2 emissions and a fair sharing of these emissions between countries.

Although the 'summit' will be exactly that - our exalted leaders meeting like so many Old Testament prophets on the mountain top - we should make our demands clear. The agreement should be for a steady-state economy that balances the interests of the people of the world, and the planet we all depend on.

[Thanks to Polyp for another brilliant cartoon. Visit his website and check out his great new animated version of the rats in the trap] Tweet

3 January 2007

Growth or Balance? Cowboy or Spaceman?

The major objective of the economy as it works now is to grow, and the more it grows the happier the politicians are. Green economists would have more sympathy with the view of the radical US environmentalist Edward Abbey that ‘Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell’. In the capitalist ideology it does not matter that economic growth is destructive and does not increase human well-being; it only matters that there is more money changing hands in the global market. There is too much emphasis on standard of living, usually measured in purely material terms, and not enough on quality of life.

For green economists growth is the major problem, not only because it is usually bought at the expense of the planet, but also because it is actually reducing our quality of life. The lifestyles we expect in the 21st century have caused the extinction of species on a massive scale, and by causing climate change are actually threatening our future as a species. Yet they have not even improved our lives. Richard Douthwaite makes this case forcefully in his book, The Growth Illusion. He gives many examples of ways in which economic growth has reduced our quality of life. Technology has reduced skill in work, lowered wage levels, and increased stress. Increased production has generated pollution and inequality, themselves the cause of physical and mental disease. Communities and personal relationships have been undermined by intensified patterns of work.

Other research has shown that econom ic growth does not increase well-being or happiness, as illustrated in the figure in the case of the USA, which is the most advanced capitalist economy in the world with the highest levels of consumption, and yet the data shows that since the early 1960s rates of happiness have been falling, while rates of psychological illness have been increasing. The figure shows rates of happiness decline in the UK since 1946 as consumption levels rise inexorably (from a lecture by Richard Layard at the LSE).

ic growth does not increase well-being or happiness, as illustrated in the figure in the case of the USA, which is the most advanced capitalist economy in the world with the highest levels of consumption, and yet the data shows that since the early 1960s rates of happiness have been falling, while rates of psychological illness have been increasing. The figure shows rates of happiness decline in the UK since 1946 as consumption levels rise inexorably (from a lecture by Richard Layard at the LSE).

This has been shown again by a study which measured increases in anxiety levels among American young adults and children between 1952 and 1993. Anxiety levels rose steadily during that time, to such an extent that the average level of a normal child today is the same as that which was found in children who had been sent for psychiatric treatment in the 1950s.

Green economics proposes a move away from a focus on economic growth and towards a ‘steady-state economy’, which is the only type of economy that can be sustainable in the long term. In the steady-state economy, the planetary frontier is respected and the earth is therefore the most scarce resource. This leads us to conclude that we should use it as wisely as possible, maximising its productivity while at the same time minimising our use of it. We should therefore focus more on quality and less on quantity.

In order to achieve the steady state we need to pay attention both to the number of people who are sharing the earth’s resources, and also their level of consumption. We should also be aware of the regenerative capacity of the planet, our only basic resource, so that non-renewable resources should not be removed at a rate faster than renewable substitutes can be developed, and our outputs of waste, including pollution, should be limited to the level where they do not exceed the planet’s carrying capacity.

The issue of resources is crucial. Economics is defined as the study of how resources are or should be distributed. Green economics suggests a whole change of perspective on our attitude to resource use, one that can be portrayed as a shift from the perspective of the cowboy to the perspective of the spaceman. The cowboy views his world as infinite and lives without a frontier in an environment where there are endless resources to meet his needs and a vast empty area to absorb his wastes. The attitude of the spaceman could not be more different. He is aware that his environment is very limited indeed. He only has available the resources that can be fitted into his small capsule, and he is only too familiar with his own wastes.

Green economists suggest that we need to leave behind the attitude of the cowboy and move towards that of the spaceman. Nowhere is this more necessary than in the world of business, where the gunslinger stills rules supreme but where viewing the earth as our only available spaceship would be a better guarantee of our survival as a species:

A businessman would not consider a firm to have solved its problem of production and to have achieved viability if he saw that it was rapidly consuming its capital. How, then, could we overlook this vital fact when it comes to that very big firm, the economy of Spaceship Earth and, in particular, the economies of its rich passengers? (Schumacher, 1973: 12). Tweet

For green economists growth is the major problem, not only because it is usually bought at the expense of the planet, but also because it is actually reducing our quality of life. The lifestyles we expect in the 21st century have caused the extinction of species on a massive scale, and by causing climate change are actually threatening our future as a species. Yet they have not even improved our lives. Richard Douthwaite makes this case forcefully in his book, The Growth Illusion. He gives many examples of ways in which economic growth has reduced our quality of life. Technology has reduced skill in work, lowered wage levels, and increased stress. Increased production has generated pollution and inequality, themselves the cause of physical and mental disease. Communities and personal relationships have been undermined by intensified patterns of work.

Other research has shown that econom

ic growth does not increase well-being or happiness, as illustrated in the figure in the case of the USA, which is the most advanced capitalist economy in the world with the highest levels of consumption, and yet the data shows that since the early 1960s rates of happiness have been falling, while rates of psychological illness have been increasing. The figure shows rates of happiness decline in the UK since 1946 as consumption levels rise inexorably (from a lecture by Richard Layard at the LSE).

ic growth does not increase well-being or happiness, as illustrated in the figure in the case of the USA, which is the most advanced capitalist economy in the world with the highest levels of consumption, and yet the data shows that since the early 1960s rates of happiness have been falling, while rates of psychological illness have been increasing. The figure shows rates of happiness decline in the UK since 1946 as consumption levels rise inexorably (from a lecture by Richard Layard at the LSE).This has been shown again by a study which measured increases in anxiety levels among American young adults and children between 1952 and 1993. Anxiety levels rose steadily during that time, to such an extent that the average level of a normal child today is the same as that which was found in children who had been sent for psychiatric treatment in the 1950s.

Green economics proposes a move away from a focus on economic growth and towards a ‘steady-state economy’, which is the only type of economy that can be sustainable in the long term. In the steady-state economy, the planetary frontier is respected and the earth is therefore the most scarce resource. This leads us to conclude that we should use it as wisely as possible, maximising its productivity while at the same time minimising our use of it. We should therefore focus more on quality and less on quantity.

In order to achieve the steady state we need to pay attention both to the number of people who are sharing the earth’s resources, and also their level of consumption. We should also be aware of the regenerative capacity of the planet, our only basic resource, so that non-renewable resources should not be removed at a rate faster than renewable substitutes can be developed, and our outputs of waste, including pollution, should be limited to the level where they do not exceed the planet’s carrying capacity.

The issue of resources is crucial. Economics is defined as the study of how resources are or should be distributed. Green economics suggests a whole change of perspective on our attitude to resource use, one that can be portrayed as a shift from the perspective of the cowboy to the perspective of the spaceman. The cowboy views his world as infinite and lives without a frontier in an environment where there are endless resources to meet his needs and a vast empty area to absorb his wastes. The attitude of the spaceman could not be more different. He is aware that his environment is very limited indeed. He only has available the resources that can be fitted into his small capsule, and he is only too familiar with his own wastes.

Green economists suggest that we need to leave behind the attitude of the cowboy and move towards that of the spaceman. Nowhere is this more necessary than in the world of business, where the gunslinger stills rules supreme but where viewing the earth as our only available spaceship would be a better guarantee of our survival as a species:

A businessman would not consider a firm to have solved its problem of production and to have achieved viability if he saw that it was rapidly consuming its capital. How, then, could we overlook this vital fact when it comes to that very big firm, the economy of Spaceship Earth and, in particular, the economies of its rich passengers? (Schumacher, 1973: 12). Tweet

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)