Easton writes that 'Blackpool is the place with the highest use of antidepressants in

England - an astonishing 1,430 prescriptions signed for every thousand

patients in the primary care trust. The PCT issued 221,000 items with

155,000 people on its books.Blackpool also emerged as England's unhappiest place in

last week's well-being survey data, with 36% of adult residents giving a

score of 6/10 or less when asked to rate how happy they were the day

before.'

Easton writes that 'Blackpool is the place with the highest use of antidepressants in

England - an astonishing 1,430 prescriptions signed for every thousand

patients in the primary care trust. The PCT issued 221,000 items with

155,000 people on its books.Blackpool also emerged as England's unhappiest place in

last week's well-being survey data, with 36% of adult residents giving a

score of 6/10 or less when asked to rate how happy they were the day

before.'The top six places in the league of anti-depressant use are all in the North-East where some of the country's most unhappy people are also to be found. By contrast, as the map shows, rates of prescribing are much lower in London, in areas that also suffer high levels of deprivation. Such correlations are always difficult to interpret, but suggest that the message about the importance of talking therapies is influential, perhaps appropriate, where the chattering classes predominate.

As well as these relationships in the data, the absolute levels of prescriptions for these mind-altering drugs are truly disturbing. More than £270m was spent on anti-depressants last year, up 23% from the previous year. This is a trend that has continued for the past tend years, with numbers of prescriptions growing from 9 million in 2001 to 24.3 million in 2001 and 46.7 million last year. The information we do not have is about how many individuals are involved, since these are numbers of prescriptions, but given the the number of prescriptions written annually for anti-depressants is now about the same as the number of adults in the country, we can assume that a massive proportion of our fellow citizens are not in their right minds.

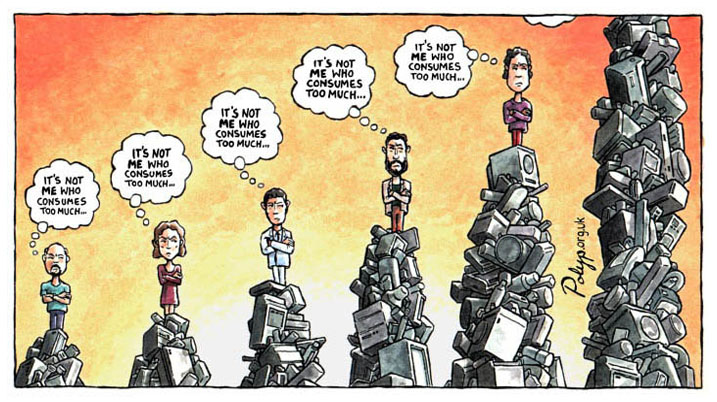

Once there was great concern amongst science fiction writers about the threat of mass medication: governments adding to water supplies large quantities of chemicals that made populations docile and passive. This would undermine citizens' ability to demonstrate political opposition, and also make them accept policies of injustice or oppression. To what extent can we suggest that the mass prescription of these drugs is already a form of such mass medication? Are levels of disempowerment, frustration and despair leading to a more voluntary version of the same threat? And why is there so little outcry from citizens in response to such blatant evidence of social failure?

. Tweet