It is quite clear that a more locally based self-provisioning economy would require a change in the pattern of land ownership from that which prevails across the world today. This is why I am a strong supporter of land value tax and land reform, both of which are policies necessary for the transition to a bioregional economy. I am currently in the north-east of Brazil in the state of Bahia. Although it was the area first settled by Portuguese colonisers and then fought over by them, the Dutch and the French, much of its land is extremely arid and away from the rivers the possibilities for agriculture are very poor. Salvador, the colonial capital, was also the centre of the slave trade and still has a strong African influence in the culture and the cuisine, and for this reason was the place where the secret martial art of capoeira was developed.

The African and slave history also gave rise to some interesting patterns of community and land ownership. Most directly we have the quilombros, communities of escaped slaves who fled into the interior and set up villages where they reproduced their African culture and created new traditions of shared use of land and systems of commons. Perhaps the experience of slavery had convinced the of the importance not only of freedom but also of distributive justice? Many of these communities survive today and the federal government of Brazil is supporting them in finding ways to legally defend their access to and use of the land.

Since its independence Brazil has, in a limited sense, taken an emancipatory approach to land ownership. If land is left unused then it reverts to the state. Other communities, known as fundos de pasto, have taken advantage of this by moving onto this state-owned land to find the means for a sustainable livelihood. These communities are made up of poor rural farmers without their own land, and people from the cities who cannot make a living there. We met Gilca Oliveira at Salvador University who is part of a research team that has produced a wealth of research on these alternative land-based communities, including those connected to end MST movement.

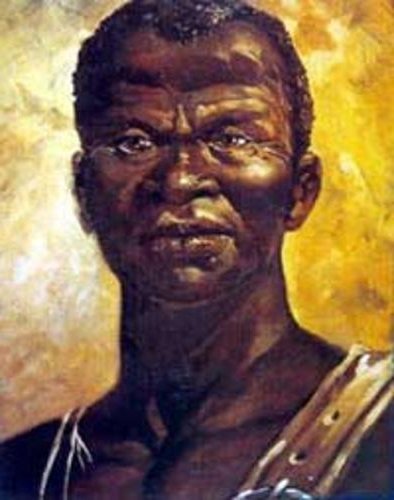

We also found here a hero to inspire resistance to neoliberalism. Zumbi dos Palmares is commemorated with a statue in one of Salvador's main squares. Zumbi was born in Palmares, the most famous and successful quilombro but was not content until all other slaves had been freed. He fought a violent struggle for emancipation and is today commemorated as the first freedom fighter for African slaves in the Americas with a national holiday in Brazil called the National Day of Black Conscience.

.