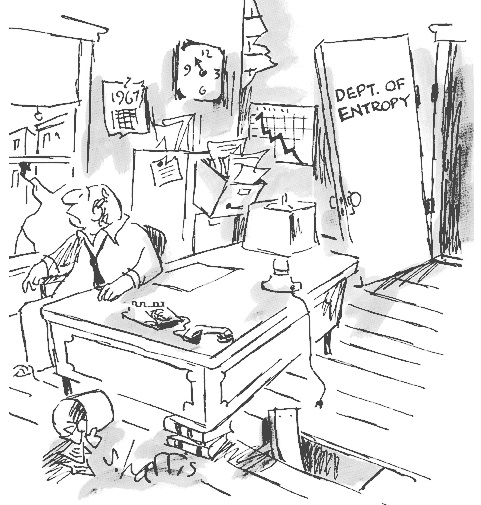

Like all economists Marx was a product of his time and his concern for the environment was limited to specific ecosystems and spaces, since the global economy had not, in the late 19th century when he was writing, reached such a scale as to threaten the whole global eco-system. Hence while Marx and Engels were critical of the effect of capitalist production on local environments, as well as the appalling conditions in the industrial cities,they failed to take seriously enough the limited nature of natural resources and the second law of thermodynamics.

Like all economists Marx was a product of his time and his concern for the environment was limited to specific ecosystems and spaces, since the global economy had not, in the late 19th century when he was writing, reached such a scale as to threaten the whole global eco-system. Hence while Marx and Engels were critical of the effect of capitalist production on local environments, as well as the appalling conditions in the industrial cities,they failed to take seriously enough the limited nature of natural resources and the second law of thermodynamics.For Marx, capitalism is a system which generates and thrives on conflict and crisis. In his own work the central conflict is between the owning and working classes and the crisis arises from the allocation of productive value, as profit extraction leaves an ever-smaller share to be distributed amongst those who work, earn and therefore have the spending power to buy goods. Once we introduce the concept of a limited planet into this framework we see that the same concepts remain useful but undergo a change of emphasis. Here is what James O'Connor has to say on the subject:

'An ecological Marxist account of capitalism as a crisis-driven system focuses on the way that the combined power of capitalist production relations and productive forces self-destruct by impairing or destroying rather than reproducing their own conditions. . . Such an account stresses the process of exploitation of labor and self-expanding capital, state regulation of the provision or regulation of production conditions, and social struggles organized around capital’s use and abuse of these conditions.'

According to Marx, within a capitalist economy every commodity has a use value and an exchange value. Exchange value is measured in terms of other commodities or in terms of money, as the universal source of ‘value’, whereas use value is the inherent value of the commodity either for immediate consumption or as in input to a further production process. Capitalists generate profits by selling the products of their factories for a price greater than that of their use value, but the workers who make the products are paid only the use value as wages. Thus ‘surplus value’ can be extracted as profit.

Marx identified a contradiction inherent within the capitalist system arising from the inability of the productive forces to generate sufficient surplus value to pay for profits and large enough incomes to buy the products of economic activity. This would lead inevitably to insufficient demand for the products of economic activity. The latter is a crisis of overproduction or under consumption which is central to the ‘first contradiction of capitalism'. The distinctly ‘ecological’ dimension to the Marxist analysis is what O’Connor terms the ‘second contradiction of capitalism’ in which capitalism expands to such an extent that it undermines its ‘productive conditions’, degrading the environment and exhausting the inputs it needs to make products and create profits by selling them.

This notion of the second crisis seems especially relevant to our economic condition just now. In fact we appear to be running into the first and second contradictions simultaneously. New markets are exhausted and the strategy of forcing ever more consumerism appears to be similarly running out of steam. Evidence of the second crisis, in terms of accelerating environmental collapse, is also increasingly evident. Tweet