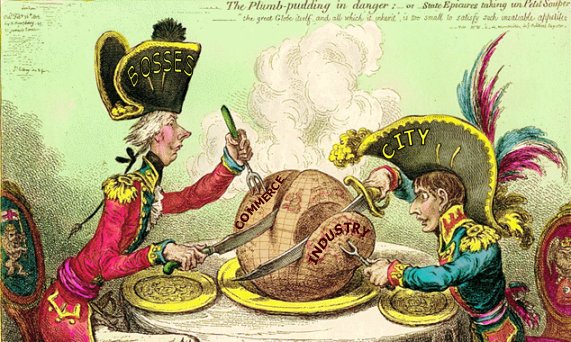

I have long cherished a vision of how a caring, sustainable economy will replace corporate capitalism. I imagine a hacienda set deep in the South American jungle. It is covered with graffiti and has broken windows--markers of previous violent attacks which failed. But the jungle is more persistent and powerful than the colonial power and green tendrils creep around the building and through the windows until it is completely overwhelmed by nature.

I was reminded of this vision when I first heard Rob Hopkins talking about bringing productive trees and plants into the city. Why shouldn't our verges and parks throng with whortleberries and wild strawberries? Here in Stroud the town council has agreed that in future trees planted in the town should be fruit-bearing. We already have one of our main cycleways planted as a linear orchard, preserving local apple species and providing fruit and conviviality in the autumn

Shortly after I read about Havana's organiponicos, or urban gardens, often roof gardens, I gave a talk in Birmingham called 'Who Will Feed the Cities?'. Walking back to the station through the urban moonscape that is central Brum I began to imagine the car parks filled with productive raised beds, and vines and fruit trees trained along the brick facades.

It has cheered me no end to see a similar vision being shared by advertising creatives. I first noticed the Baxters Farmers' Market soup advert, where the urban cat is replaced by a piglet and a bride's bouquet is made of carrots. This was followed by an advert for E-On where giraffes invade the office and a beaver is found in the water-cooler.

It seems to me that this is the opposite impulse to that which continues to drive well-paid executives into the countryside, which they immediately neutralise and suffocate with their 'city ways'. How welcome to see an invasion of the city by revolting peasants and their filth. Tweet