I remember learning in school about the Inuit (we called them eskimos then, of course) and how they used every last part of the caribou: skins for blankets, hides for wigwams, sinew for thread, bones for needles. Not a scrap was wasted, we were told, and we marvelled at this. Such a contrast to the way we lived even then.

I spent this past weekend with my good friends Lydia and Robert, co-creators of Thrift Cottage, and had the usual restful and inspiring time. Robert's knowledge of the natural world - trees and woodworking are his speciality - is something he has learned from joiners and carpenters he has worked with who come from a different era. He is always full of wisdom about his craft that is humbling to somebody like me who lives from their brain.

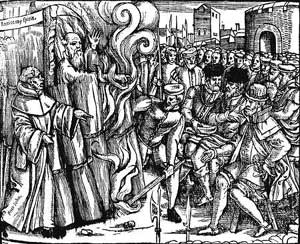

This weekend's gem was a short history of faggots and tallow. These two fundamental parts of the lives of our ancestors just a generation or two ago have slipped out of consciousness. The only picture I have ever seen of a faggot is on the woodcut from Foxe's Book of English Martyrs, but I was interested in converting garden and agricultural waste into fuel and so asked Robert how it is done.

His brother is the tallow man - he recreated by laborious practice the means of extracting this most useful substance from sheep's testicles (didn't I say everything had a use?) following instructions he found in a book from the 1960s. Boatbuilders and joiners are still using blocks of this natural lubricant. Robert says it is the best way of easing a screw into a piece of oak and the only lubricant that resists the tree's attempt to use its natural juices to keep it there. That puts high technology into its place. Tweet