This title really has nothing to do with the subject of this post - I just think it is such a great one I thought I would share it. And that

is the theme of this post. In passing I might mention a discussion we recently had in an academic seminar that

is relevant to this title, which belongs to a book by Marilyn Strathern. The subtitle is 'Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia' - it is social anthropology and if I read it I'm fairly sure I would not be able to understand, although it might give me a warm feeling that I was in good sisterly company.

The debate concerned whether or not gender is a significant designator of personhood compared with, for example, hair colour. During the discussion nobody could make a rational argument about why it was and I found myself in that embarrassing situation of not being able to avoid seeing the funny side when in a small group of people. I was assaulted by the mental image of several brown-haired women struggling to use a urinal. This is the sort of thing that passes the time in the academic day.

Strathern struggles with unquestioned assumptions that Western anthropologists make about Melanesian society - and Western society - in its attitudes to gifts and women. I have my own struggles with gift-giving - a result of my attempt to reduce my impact on the planet and my own personal trait for being exceptionally mean. I can never be sure which predominates when I do - or don't - buy gifts for friends whom I love dearly.

A friend who lives on bread and scrape recently gave me a gift which epitomises the truth of the adage that 'It's the thought that counts'. We'd been together at a workshop at Climate Camp Cymru. I was responsible for the fuzzy-huggy closing bit and had decided to get everybody holding hands and send a bolt of energy around the circle. This didn't work that well and so we switched to the hokey-cokey. Apparently this was the most blogged about asepct of the workshop.

Which is fine - we are modelling a better life - the hokey-cokey is low-carbon fun and will clearly have a central role in any green society. The gift was a t-shirt asking 'What if the hokey-cokey really is what it's all about?' It could just be.

And while we are on the subject of gifts, a couple of co-conspirators have recently produced delightful books that I would like to share with you and that you might like to share with friends and family who have particular reasons to receive gifts, once you've been through all that problematic carbon-related angst, as already described.

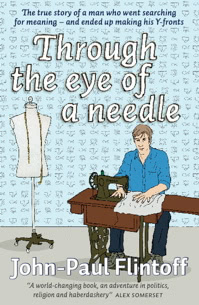

First, we have John-Paul Flintoff's

Through the Eye of a Needle: The true story of a man who went searching for meaning – and ended up making his Y-fronts. John-Paul is charming and so is his book. As an intellectual might say, it works on lots of different levels. There is a spiritual journey here, but also lots of hi-jinks and good jokes.

This is the way the world changes, gently, through Woman's Hour and in second-hand clothes shops, not the Today programme and no. 10. At least, I very much hope this is the case. How delightful it would be if Gordon Brown were revealed as wearing underpants made from nettles - that might explain why he always looks so uncomfortable.

The second book is more hard-hitting. In this world of ubiquitous cognitive dissonance how can we be anything other than

Speechless? Polyp's fame has increased steadily since his origins as house cartoonist for New Internationalist. Like a really good comedian he can sum up everything that has been causing you frustration and rage in one drawing - and make you laugh about it.

Sometimes the laughter here is fairly dark and hollow, and the cartoons are so complex you could easily spend the whole duration of a bath perusing only one. On that basis the book could keep you going for a whole year - assuming you have cut down your bath-rate to reduce your carbon emissions. It would make a good present for friends (an increasingly large number of younger ones) who don't read.

So far I have only considered the last resort in a financial sense, but what about the ecological crisis we are facing: the ultimate situation of last resort. Surely it is time for the government to act as borrower of last resort and produce a massive spending package to create the infrastructure and home renovation projects we need to achieve the carbon reduction targets that are now enshrined in law? Mad as it may seem, if you insist on creating money as debt, that is the only way that we are ever going to be able to buy ourselves a future.

So far I have only considered the last resort in a financial sense, but what about the ecological crisis we are facing: the ultimate situation of last resort. Surely it is time for the government to act as borrower of last resort and produce a massive spending package to create the infrastructure and home renovation projects we need to achieve the carbon reduction targets that are now enshrined in law? Mad as it may seem, if you insist on creating money as debt, that is the only way that we are ever going to be able to buy ourselves a future.