A guest post by Penelope Ciancanelli

Most of what needs to be known about the suicide of internet activist Aaron Swartz has been written in the hundreds of stories easily found on the internet. I commend them all to you because there is surprisingly little duplication and a great deal of evidence explaining why so many privileged and educated people in the US now fear rather than respect its criminal justice system. Indeed if any good is to come out of this case (which is, in itself to be doubted), it will be in greater public scrutiny of a criminal justice system that has long been out of control.

Few of the facts in the Swartz case are in dispute. Swartz admitted he illegally downloaded hundreds of scholarly articles from JStor via a net-book which was surreptitiously connected to a mainframe at MIT that supports access to its library’s subscription services. Upon discovery of the hack by the private security employed by MIT, the case was turned over to the police service of the city of Boston who then--and here it gets a big vague--gave it over to the secret service of the US federal government. Why the secret service involvement?

According to the mission outlined on the website of the US secret service, their agents get involved when there is significant economic or community impact, organized criminal groups involving multiple districts or transnational organizations are involved or a criminal scheme involves new technology. What Swartz did has nothing to do with their self stated mission.

However since 9/11, the various pieces of badly drafted legislation passed in the Bush presidency to fight terrorism have allowed agency mission creep of considerable proportions. Indeed, on a quiet day at the Boston division of the secret service why not have a nosy around incidents at MIT. Maybe that is all that happened; or perhaps a source at MIT called their office, the service peoplehad nothing better to do and the rest, as they say, is charges of 35 years in prison.

Te secret service involvement did not prevent JStor (the injured party) from refusing to press charges, once it understood the nature of the hack. However, MIT, where the hack took place, was not as clear-minded and its managers dithered. Perhaps this dithering encouraged the secret service to further involvement and taken together led the federal prosecutor for this district, the US district attorney Carmen M Ortiz, to believe the case had greater importance than it had--all of which is pure speculation. As a result, any link between this suppression of secret service involvement and the vigor with which the US district attorney for Massachusetts (Carmen Ortiz) pursued the case against Swartz is impossible to assess.

However, her zeal does stand in strong contrast to the general tenor of prosecutorial life under the agency’s leader, Attorney General Eric Holder. He has generally preferred settling out of court and nearly all the white collar crimes of the Wall Street Banksters have been settled rather than tried.

This contrast between prosecutorial zeal at the district level and lassitude at the federal level is even more odd when one considers Ortiz and Holder have known each other since the early 1980s when the pair worked together on Abscam (a convoluted FBI sting operation aimed at prosecuting influence peddling by state and federal officials). Moreover, more than anyone Eric Holder is responsible for Ortiz’s appointment as the Massachusetts District Attorney. One would have thought the reason for choosing her was his expectation she would share his stance towards plea bargaining rather than jailing white collar criminals. In the Swartz case, Ortiz acted opposite to his general stance and that is what draws attention.

Tere is no doubt the tragedy of this case is the driving to distraction of a gentle genius by a rather insecure and truculent district attorney who finds it sufficient to defend her actions as follows: ‘Stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars’, she said. ‘It is equally harmful to the victim whether you sell what you have stolen or give it away.’

It is as if no amount of schooling in the law, in life and in court is allowed to diminish the simple-minded clarity of a rather simple-minded prosecutor. Bit of a shock to realize she might very well believe what she said despite the fact there was no victim: JStor acknowledged, after the fact, the need to make academic papers more easily available to the public taxpayers who paid for most of their production. The authors of those papers had long ago given over their copyright to the publisher, as a condition of publication. And the publishers long ago gave ownership of the papers to JStor. No one was injured.

It would be easy to attribute the actions of Ortiz to some grand federal plan to prevent digital piracy at any cost. However the facts in the case make a smaller more parochial more pathetic kind of sense. A truculent and rather unsophisticated prosecutor endowed a trivial case with an importance it did not have because important people were involved and because the young offender pissed her off. He pissed her off because he was privileged, smart and spoke truth to power, something she never had the luxury of doing. The lesson here is the banality of the probably motive for the evil actions. Envy with a badge, a gun and privileged access to courts ought to make us all uneasy.

Are there any open access lessons in this? You bet. Those of you at universities, go talk to the head librarian about serials prices, see if the librarian has records for the price hikes for the past decade. Ask yourself: how does it happen that what I write/referee/edit is owned by a multinational media conglomerate who charges my university multiples of my salary to read what I and my colleagues have written? Open access matters and there is a duty to find out why.

One place to start is Ciancanelli, P. (Re)producing universities: knowledge dissemination, marketpower and the global knowledge commons in the World Yearbook of Education. Sage. 2008: 67-84. I hope you can find your way past the pay-wall but if not, contact me direct: pciascuno@gmail.com

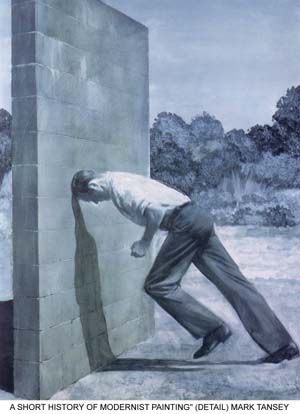

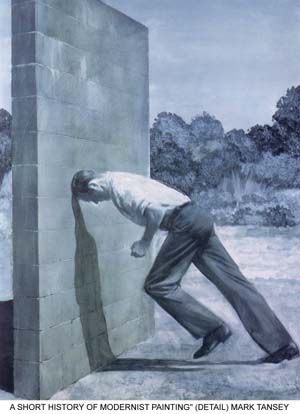

Editor's note: although some delightful images of Aaron Schwartz are available on the web the software used for this website would not allow me to use any of them because of IP restrictions. How sad and desperately ironic.

.

Tweet

All other green campaigns become futile without tackling the economic system and its ideological defenders. Economics is only dismal because there are not enough of us making it our own. Read on and become empowered!

Showing posts with label intellectual property. Show all posts

Showing posts with label intellectual property. Show all posts

17 January 2013

24 May 2008

Sharing the knowledge

Now that universities have become corporations and higher education is just another sector of our globally competitive economy, why should we co-operate with each other and share our knowledge. Shouldn't we rather be hoarding it and selling it for the highest price?

This is a particularly disastrous strategy for knowledge management at a time of crisis when knowledge about how to manage our affairs sustainably needs to be spread as rapidly as possible. A recent conference of researchers exploring the Transition Towns in the UK came up with an answer to this problem: the knowledge co-operative.

Many well-motivated researchers laugh in the face of intellectual property law and proudly proclaim their willingness to give away their knowledge. This is missing the point in two ways. First, if you have signed a standard university contract your knowledge doesn't belong to you anyway. Even though all our best ideas arise in the bath or on the bus everything you have ever thought belongs to your employer.

More seriously, if we don't try to maintain control over this knowledge, then others probably will. Just like the neem tree, vital insights into how sustainable communities actually work could be controlled by corporations and sold back to us - just as our research papers are. Nothing could be more iniquitous than the fact that we review each other's work for free, edit our own work, format and typeset it - but then cannot gain access to each other's work without subscribing to journals whose profits go to publishing corporations.

The sustainability knowledge co-operative will be a membership organisation which academics and research centres can join. They will undertake to share knowledge freely with others in the co-operative who will not make a profit from it. Their own contributions can be protected by creative commons licences so that if somebody is likely to make a profit from their ingenuity then they can negotiate a share. Some knowledge will be so important that - like Volvo's three-point seatbelt or pencillin - it will be given to the world for free, but it will not be available for others to copyright.

Knowledge is a common resource, and knowledge created by publicly funded universities should belong to the public. However, in a free market, we cannot leave this knowledge floating freely. We need to constrain it legally in a way that facilitates its sharing and empowers those who create it rather than the corporate knowledge factories which employ them. Tweet

1 May 2007

Assumptions of Perfect Competition: Lesson 3

Given the savagery with which corporations defend their right to control the markets they operate in, the third assumption of a perfectly competitive market seems fairly extraordinary.

Assumption 2: There is complete freedom of entry into the industry for new firms

This assumption follows directly from the first and is necessary to ensure that there continues to be a large number of buyers and sellers so that competition between them occurs. In order for entry and exit to the marketplace to be free there must be no ‘barriers to entry’. As just explored, it is obvious that in the market for complex products, the need to invest in R&D, to prepare a product for the market, and then to advertise it all create barriers too huge for all but the largest corporate investor. James Dyson has described in detail his experience of trying to break into the market for vacuum cleaners, with a new product which he wanted to sell himself rather than selling the idea to one of the corporations controlling that market.

The whole concept of ‘intellectual property’, enshrined as TRIPS (Trade-Related Intellectual Property) in the WTO agreement makes a mockery of free entry into the market, since patent or licensing laws will operate to restrict this assumption. So one of the central assumptions used to argue that markets are the ideal way to distribute goods relies on the fact that producers can have free access to information about products they might wish to produce, that the inventor of the process cannot use the law to protect his right to extract profits from that invention while preventing others from producing it more cheaply. That, in fact, that 564 pages of Blackstone’s Statutes on Intellectual Property d o not exist. In reality, of course, this is the kind of law corporations use to protect their profits. How surprising that an organisation like the WTO, which claims to be the foremost global promoter of ‘free’ markets, in fact defends the right of corporations to extract profits in this way that wholly invalidates the free operation of markets.

o not exist. In reality, of course, this is the kind of law corporations use to protect their profits. How surprising that an organisation like the WTO, which claims to be the foremost global promoter of ‘free’ markets, in fact defends the right of corporations to extract profits in this way that wholly invalidates the free operation of markets.

We may take the example of the pharmaceutical industry, since it is a clear case where every moral pressure, never mind the strictures of a genuinely free market, suggests that knowledge about how to cure disease should not be restricted. Patents have long been used in the pharmaceutical industry to protect the fruits of research. The justification used is that, if companies could not be guaranteed the right to be the sole profiteer from their discoveries, they would not invest the money in the initial research. However, when faced with dire humanitarian need few think that the global protection of what is referred to as ‘intellectual property’ under the TRIPs agreement, can be maintained. This is why, with 25 per cent of its people of working age being HIV-positive, the South African government decided to ignore international law and import generic AIDS drugs from India. The price difference is staggering—$350 for a year’s supply compared with $10,000 for the branded medicines—so a poor country like South Africa had little choice. Under the TRIPs agreement South Africa was clearly able to justify its actions under clauses exempting countries facing public-health disasters, but its actions were legally challenged by the US trade representative and action was taken against the government of South Africa by the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association. The courage of the government was rewarded and the PMA eventually withdrew its case in 2001, coming to a deal with the government over reasonable pricing and availability of AIDS drugs.

The reality in the pharmaceutical market, as in many markets, is that businesses will produce what they can make a profit from, not what is in the public interest. This is why there are no high-tech cures for sleeping sickness and malaria, which poor people die from, while there are a superfluity of treatments for the concerns of the affluent, from skin products to slimming pills. It is a recognition of the fact that research for profit is not directed in the public interest that leads to the awarding of research grants for the development of a range of important recent drug successes.

A report from the US Congressional Joint Economic Committee in May 2000 established that 7 of the 21 most important drugs introduced in the US between 1965 and 1992 (including tamoxifen, AZT/zidovudine, Taxol, Prozac and Capoten) were developed with the help of federal funds. AZT, the leading anti-AIDS drug, was originally synthesized in 1964 as a result of a National Cancer Institute grant. However, GlaxoSmithKline determined the drug’s anti-AIDS properties and were granted a patent for this use, and hence profited from its worldwide sale. Many of these drugs that are so jealously guarded have been developed partially, often to the extent of half the funding, by public money. And yet the ‘intellectual property’ reverts to the corporations and we, the public who funded the research, have to pay them for the benefits of the knowledge they developed at our expense.

The other side of the free-entry-and-exit coin is the need for ‘factors of production’, i.e. labour and capital, to be perfectly mobile. Just in personal terms it is clear that labour is far from mobile: rrestrictions range from family or neighbourhood ties to the loss of pension rights’. But the most glaring ‘restriction’ is found in the strict immigration rules that govern freedom of movement of labour. What is the value of basing a claim to the superiority of the market on the fact that workers can move freely to better paid jobs in a world where they are not actually allowed to enter Britain, are condemned as economic migrants and, if they succeed in entering, put in gaol as illegal immigrants or deported? Even in a labour-market with apparent free movement of labour, as the EU has been since 1992, there is actually very little movement of workers from one country to another, since they are dissuaded by language and cultural barriers.

The devastating consequences of genuine free movement of labour can be assessed by comparing the minimum wage in the UK with the sorts of wages paid to workers in the Chinese SEZs (special economic zone, or specially exploitative zone) in Guangdong exposed by Corporate Watch. A shoemaker there earns only £40 per month of 14-hour, 7-week days, out of which s/he has to pay for food and bedding. It is the working conditions faced by people like this that turn them into economic migrants, and their desperation and willingness to be exploited that frightens European governments into undermining the free market they officially support by preventing their freedom of movement into our labour market. Tweet

Assumption 2: There is complete freedom of entry into the industry for new firms

This assumption follows directly from the first and is necessary to ensure that there continues to be a large number of buyers and sellers so that competition between them occurs. In order for entry and exit to the marketplace to be free there must be no ‘barriers to entry’. As just explored, it is obvious that in the market for complex products, the need to invest in R&D, to prepare a product for the market, and then to advertise it all create barriers too huge for all but the largest corporate investor. James Dyson has described in detail his experience of trying to break into the market for vacuum cleaners, with a new product which he wanted to sell himself rather than selling the idea to one of the corporations controlling that market.

The whole concept of ‘intellectual property’, enshrined as TRIPS (Trade-Related Intellectual Property) in the WTO agreement makes a mockery of free entry into the market, since patent or licensing laws will operate to restrict this assumption. So one of the central assumptions used to argue that markets are the ideal way to distribute goods relies on the fact that producers can have free access to information about products they might wish to produce, that the inventor of the process cannot use the law to protect his right to extract profits from that invention while preventing others from producing it more cheaply. That, in fact, that 564 pages of Blackstone’s Statutes on Intellectual Property d

o not exist. In reality, of course, this is the kind of law corporations use to protect their profits. How surprising that an organisation like the WTO, which claims to be the foremost global promoter of ‘free’ markets, in fact defends the right of corporations to extract profits in this way that wholly invalidates the free operation of markets.

o not exist. In reality, of course, this is the kind of law corporations use to protect their profits. How surprising that an organisation like the WTO, which claims to be the foremost global promoter of ‘free’ markets, in fact defends the right of corporations to extract profits in this way that wholly invalidates the free operation of markets.We may take the example of the pharmaceutical industry, since it is a clear case where every moral pressure, never mind the strictures of a genuinely free market, suggests that knowledge about how to cure disease should not be restricted. Patents have long been used in the pharmaceutical industry to protect the fruits of research. The justification used is that, if companies could not be guaranteed the right to be the sole profiteer from their discoveries, they would not invest the money in the initial research. However, when faced with dire humanitarian need few think that the global protection of what is referred to as ‘intellectual property’ under the TRIPs agreement, can be maintained. This is why, with 25 per cent of its people of working age being HIV-positive, the South African government decided to ignore international law and import generic AIDS drugs from India. The price difference is staggering—$350 for a year’s supply compared with $10,000 for the branded medicines—so a poor country like South Africa had little choice. Under the TRIPs agreement South Africa was clearly able to justify its actions under clauses exempting countries facing public-health disasters, but its actions were legally challenged by the US trade representative and action was taken against the government of South Africa by the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association. The courage of the government was rewarded and the PMA eventually withdrew its case in 2001, coming to a deal with the government over reasonable pricing and availability of AIDS drugs.

The reality in the pharmaceutical market, as in many markets, is that businesses will produce what they can make a profit from, not what is in the public interest. This is why there are no high-tech cures for sleeping sickness and malaria, which poor people die from, while there are a superfluity of treatments for the concerns of the affluent, from skin products to slimming pills. It is a recognition of the fact that research for profit is not directed in the public interest that leads to the awarding of research grants for the development of a range of important recent drug successes.

A report from the US Congressional Joint Economic Committee in May 2000 established that 7 of the 21 most important drugs introduced in the US between 1965 and 1992 (including tamoxifen, AZT/zidovudine, Taxol, Prozac and Capoten) were developed with the help of federal funds. AZT, the leading anti-AIDS drug, was originally synthesized in 1964 as a result of a National Cancer Institute grant. However, GlaxoSmithKline determined the drug’s anti-AIDS properties and were granted a patent for this use, and hence profited from its worldwide sale. Many of these drugs that are so jealously guarded have been developed partially, often to the extent of half the funding, by public money. And yet the ‘intellectual property’ reverts to the corporations and we, the public who funded the research, have to pay them for the benefits of the knowledge they developed at our expense.

The other side of the free-entry-and-exit coin is the need for ‘factors of production’, i.e. labour and capital, to be perfectly mobile. Just in personal terms it is clear that labour is far from mobile: rrestrictions range from family or neighbourhood ties to the loss of pension rights’. But the most glaring ‘restriction’ is found in the strict immigration rules that govern freedom of movement of labour. What is the value of basing a claim to the superiority of the market on the fact that workers can move freely to better paid jobs in a world where they are not actually allowed to enter Britain, are condemned as economic migrants and, if they succeed in entering, put in gaol as illegal immigrants or deported? Even in a labour-market with apparent free movement of labour, as the EU has been since 1992, there is actually very little movement of workers from one country to another, since they are dissuaded by language and cultural barriers.

The devastating consequences of genuine free movement of labour can be assessed by comparing the minimum wage in the UK with the sorts of wages paid to workers in the Chinese SEZs (special economic zone, or specially exploitative zone) in Guangdong exposed by Corporate Watch. A shoemaker there earns only £40 per month of 14-hour, 7-week days, out of which s/he has to pay for food and bedding. It is the working conditions faced by people like this that turn them into economic migrants, and their desperation and willingness to be exploited that frightens European governments into undermining the free market they officially support by preventing their freedom of movement into our labour market. Tweet

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)