What is government borrowing?

When I learned my economics this was called the PSBR or ‘public sector borrowing requirement’ but it has since been renamed the PSNCR or ‘public-sector net cash requirement’. These renamings usually have political intent and in this case I’m guessing it it is to get away from the unhealthy concept of ‘borrowing’. This is the annual amount that central government, local government and the public services borrow each year to keep themselves going. The ‘national debt’ is the accumulated total money that government has borrowed over the years which it couldn’t afford to pay back. Sometimes it goes down but, since the Bank of England was set up in 1694, the trend has been steadily upwards.

Where does this money come from?

The government has three sources of revenue: taxation, where it takes money directly from companies or individuals; from selling government bonds; and from printing money directly. The last of these has become increasingly unpopular since the Second World War, but is in fact a liberating way for government to create money without putting anybody into debt. At present government only creates note and coin in this way, which represents around 3% of total money.

What role do gilts play?

What role do gilts play?Gilts is just another name for government bonds—gilt-edged securities—because they are safer than anything else, since so long as the country doesn’t sink the government is bound to pay interest twice a year on them. Investors will get their money back after a certain fixed time specified on the bond, however before that time the value of the bonds will fluctuate, depending on the rate of UK interest rates. If interest rates are expected to fall, investors will tend to buy bonds because they are likely to be worth more in the future.

Who is stumping up?

This is an interesting question. Why should anybody want to invest in UK bonds when our economy is clearly short of a paddle and in unpleasant surroundings? If you are somebody with plenty of money to invest your primary concern at the moment is going to be security, so bonds might look quite attractive compared to stock in a corporation. So your gamble is likely to be about which countries bonds are most attractive, based on your view of how the interest rates of countries are going to move. Given that all countries are cutting interest rates one would assume that all national bonds are equally (un)attractive.

This question makes it clear how we are all entangled in the same mess. China owns a vast quantity of US treasuries (their name for government bonds) and if it chose could sell these and destroy the US economy. But if it did that it would lose its main export market and its own economy would falter. So, on a global basis, owning more stock doesn’t necessarily make you more powerful. Remember the old adage: if you own £1m. the bank owns you, but if you owe £1bn you own the bank!

This question makes it clear how we are all entangled in the same mess. China owns a vast quantity of US treasuries (their name for government bonds) and if it chose could sell these and destroy the US economy. But if it did that it would lose its main export market and its own economy would falter. So, on a global basis, owning more stock doesn’t necessarily make you more powerful. Remember the old adage: if you own £1m. the bank owns you, but if you owe £1bn you own the bank!Why should anybody buy our national debt?

Your ability to sell you bonds depends on the general perception of your reliability as an economy. This was the problem Iceland faced, being a volcanic rock with a population the size of Bristol and no resources other than fish and hot water, it couldn't realistically stand behind the debts that its entrepreneurs had racked up. A country’s ability to do this depends on its perceived power in the global capital market. The most powerful economies are those that control the ‘reserve currencies’—the dollar, euro, pound, yen and Swiss franc. These are currencies other governments hold their national reserves in and therefore are good for massive debts. The US is in a special position because in 1944 it negotiated that its currency would actually be held as equivalent to gold in reserve terms. It had to maintain a link between its currency and gold to back this up, but broke that rule in 1971 and since then has been able to print paper and get massive amounts of resources in exchange for it.

The UK is therefore in a strong position in increasing its national debt. One important way of measuring this is comparing the amount our economy produces each year with the size of our national debt—the so-called debt-to-GDP ratio. Ours is currently around 40% and is predicted to go above 50% as the recession deepens. Argentina went bust in 2001 with a debt-to-GDP ratio of less than 40% and a healthy level of exports and resources. The difference was it did not have a reserve currency and when speculators targeted the peso the government could not defend it. So it is really about political rather than economic power.

Who calls in the debt, both to the banks and the government? When?

So long as government continues to pay the interest it owes on the bonds there need never be any ‘calling in’ of the debt. There never has been since this malarkey started in 1694. When the bonds come to the end of their life, the government creates new ones to pay back the people who bought the old ones. The same people probably buy the new ones—at least to some extent.

Aren’t we the taxpayer then going to pay for what we’ve lent?

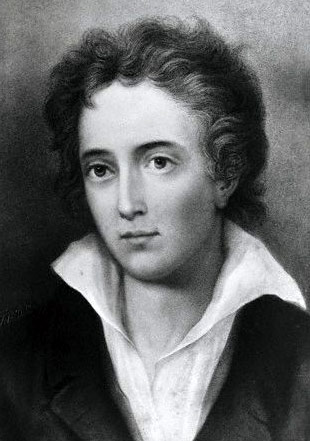

Yes. Absolutely. This is why Percy Bysshe Shelley called the national debt ‘a system for transferring income from the labouring segment of the population to those who’ had money to lend to government and would thus accrue interest, and who profited from government expenditure in wars. It is a way of transferring money from the poor to the rich and always has been. Amazing how they’ve got away with it for so long isn’t it? I wonder how many people will wise up now.

Yes. Absolutely. This is why Percy Bysshe Shelley called the national debt ‘a system for transferring income from the labouring segment of the population to those who’ had money to lend to government and would thus accrue interest, and who profited from government expenditure in wars. It is a way of transferring money from the poor to the rich and always has been. Amazing how they’ve got away with it for so long isn’t it? I wonder how many people will wise up now.The banks seem to want to have their cake and eat it; they can take our money but still decide that we’re too much of a risk to invest in?

What is happening with the banks is a bit different. They do not lend pre-existing money but create money through a multiplier process—because they never expect all depositors to come back for their money at the same time. But to accept other banks’ promises to pay requires mutual confidence between the banks and this is lacking. You can see it as rather like a pyramid-selling scheme. While you can find new buyers it works fine, but when the market is exhausted the people at the end of the chain lose their money and the system collapse. That is what just happened. The only way out is for banks to believe in each other again—which is what the government is trying to ensure. Then they will bring money into existence again and the whole upward spiral can start again. So, to be fair, I don’t think the government gave money to the banks to be passed on in loans, but rather to reboot the system. This doesn’t appear to have worked and banks are only following their rulebook in not lending their own money.

Why does government policy on banking keep changing?

When the Rock started the rot the government still believed it could stop the rapid downward spiral if it stood behind just this one bank, initially just in theory. But the bad debts were so frightening to the banks that this didn’t work and it was clear that other banks—-perhaps all the banks—could go down like dominos. At that point it took complete control of Northern Rock. At each stage it has in mind to achieve the rebuilding of confidence as cheaply as possible. Supporting Northern Rock did not rebuild confidence so then they moved to the full-scale bail-out. This also doesn’t seem to be working, since credit is still tight. In a world where businesses rely on debt to survive this is now damaging the real economy that provides goods and services. So the economic bail-out is the latest stage. But it is still jump-starting and is by no means guaranteed. We will have to pay the damage whether or not it succeeds.

There is still no plan to address the problem at source, which is the gap between nominal value in terms of finance and real value in terms of what our economy actually does. On a global basis, 98% of the transactions that take place everyday have nothing to do with the real economy, they are just gambling in the casino economy, most of it speculation in the possible future rises and falls in the value of the various currencies. This is a much more efficient way to make money than actually making stuff.

This sounds like a merry-go round rather than a rescue plan?

It always was a merry-go-round. That is how finance works. It has worked fairly well for the 200-odd years that we have lived in the capitalist economy, but with periodic booms and busts. To achieve a steady-state economy would also require stable money. Government could just create that money by fiat—we would believe it because we believe the government, just like investors believe in the value of government bonds. But this would be money creation without debt. The difference would be that the process would not require our work to pay back the national debt and would therefore undermine the work-money nexus at the heart of capitalism. Sounds tempting doesn’t it?!

Surely the global financial system as currently configured is on any accepted measure a write off?

I agree with you about this. I think the only solution is to go for the full-scale jubilee and go back to the Bretton Woods conference table. We could then reinstate the two major planks of Keynes’s plan at that time: balanced budgets between nations with fines for deficits and surpluses, and a neutral international currency so that no government had the ‘reserve currency’ advantage. In addition I think we could tie this currency to an agreement on climate change and therefore stitch the environmental crisis into the solution too. The main difference between then and now is the liberalization of finance so that it is not under national control. This needs to be reversed with the reintroduction of credit and exchange controls. Without control of finance how can a government claim to be sovereign? And how can we imagine we live in democracies?

No comments:

Post a Comment