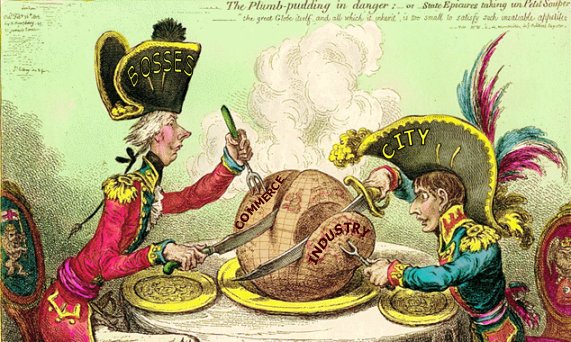

Firstly, the foolishness of 'economic development' within a capitalist mindset was made manifest. Take the town of Tewkesbury. Lying at the confluence of the Avon and Severn Rivers it is always going to be at serious risk of flooding. The Abbey there has stood and remained dry for 700 years, but this year it flooded. The reason was unwise building further up the river, removing the possibility of the water moving onto its natural floodplain. Something those who lived in the Dark Ages were surprising enlightened about.

When new housing developments are put in the flood-plain the supermarkets that enable the profiteering are given a superior position on a concrete plinth. Like the cathedrals of old they are now the most revered constructions. Unfortunately, in Tewkesbury this meant that when the flood came people in Morrisons were stranded on an island and had to spend the night in the cafeteria.

Tewkesbury has another flood-plain development planned. This July it was called The Watermeadows but its name has miraculously changed to The Meadows during the summer.

Surviving the floods was a salutory experience, and a very uplifting one after the initial panic had subsided. We amazed ourselves with our resourcefulness, as we found Heath-Robinsonesque ways to channel rainwater into our toilets and wash five heads of hair with half a bucket of water. We found out who our neighbours were (and look after the vulnerable ones) and we found out where our electricity and water came from (amazed that we had never known!)

We were instructed not to flush our toilets with drinking water - some of us realised that this is in fact what we do everyday and thought about ways to make our water use and distribution system less wasteful in future. The most important thing we learned from the flood was that the greatest resource we have is each other, and that in a crisis we do look after each other.

Looking further afield, I was interested to see how attitudes to economic development have changed in Thailand, partly as a result of the tsunami. The country has turned its economy in the direction of sufficienty rather than export-led growth. They are building self-reliance and reinforcing their local communities, as well as finding inspiration from the workings of nature.

2007 has been the year when many people - sadly not many politicians - have started to think seriously about the economics of climate change: about how it will affect their ways of finding daily necessities and the way they interact with their environment and each other.